“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

Shakespeare was a man for all seasons, but was his Hamlet correct?

Let’s take a common item such as corn, for example. It has no moral compass. It simply exists, thanks to the selective cultivation over thousands of years by Native American farmers starting in Mexico from a humble grass.

The Mayans and other Indians considered corn an object of good, so much so that it was revered. In the Mayan creation story, humanity was formed by the dough ground from corn at the hands of the deities (O’Leary).

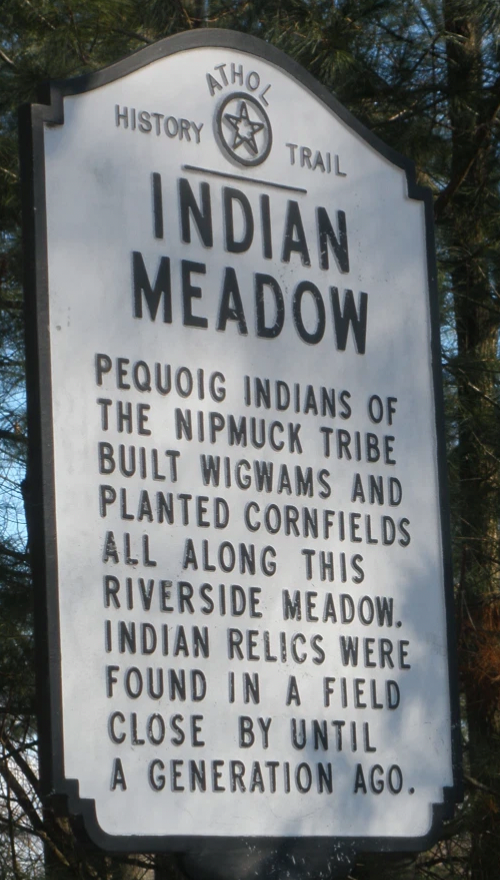

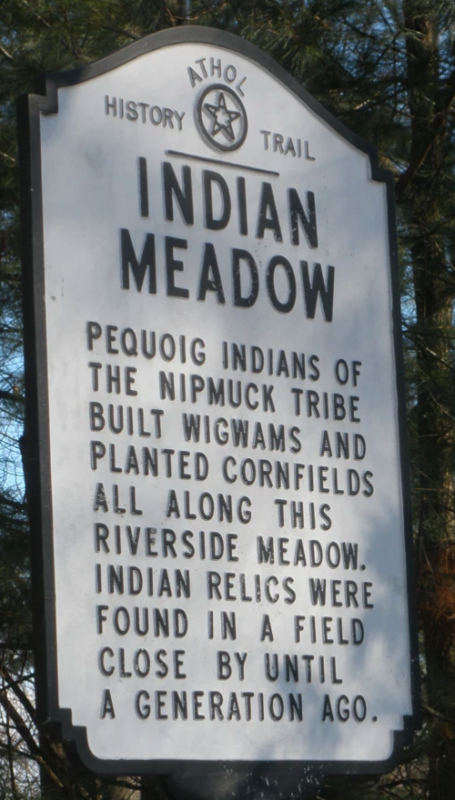

The corn farming Pequoig Indians of Massachusetts are still remembered in the small town of Athol in central Massachusetts with a highway historical marker close to the Millers River, the waterway they relied on for cultivation.

“Pequoig Indians of the Nipmuc Tribe built wigwams and planted cornfields all along this riverside meadow. Indian relics were found in a field close by until a generation ago” (Human). [See photo]

With Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, an explosive exchange of people and crops, including corn, was triggered. By the 1600s, it was being cultivated in Africa for the first time and by the 1700s grown over much of the continent.

Corn had arrived with the Portuguese at their trading forts and was soon planted in African farmers’ fields. The people found corn to provide plenty of sustenance and energy. But that wasn’t its only selling point. Because of a mountainous ancestry, corn grows to maturity relatively quickly, plus has the added advantage of not requiring lots of labor. All these features for the good?

Yes and no. According to researchers Cherniwchan and Moewnow-Cruz in the Journal of Developmental Economics, more food in the form of the grain led to some increases in the African population. In and of itself, not a bad thing, except that the rising number of people accounted for some of the increase of those sold into slavery (Cherniwchan).

Back in the Americas, corn was used in place of currency in cash strapped colonial North America, sometimes for evil yet other times for good. After King Philip’s War, some of the captured Native Americans in Rhode Island were sold into bondage for bushels of Indian corn.

Indian children from infancy to five years old were sold into service until their thirtieth birthdays. Youngsters from five to ten years old were held until reaching two years shy of their thirtieth, while boys and girls ten to fifteen were bound to service until twenty seven years old. Teenagers between fifteen and twenty were held until reaching twenty six. Young adults in their twenties were held for eight years and those older, seven. In addition to corn, many Native American captives were sold in exchange for wool and silver (Bicknell 501). Although leading similar daily lives to enslaved Blacks, they could look forward to their futures, no matter how distant.Sometimes corn was valued higher than human life. When Jonathan Heyward died in Mendon, his probated inventory listed “one old negro fellow with his Clothes Bed and Beding” at about one pound sterling. Contrast this with “225 bushell[s] of Indian and English corn” at over 24 pounds (Worcester). Young children enslaved in the South were lulled to sleep with a lullaby about their father plowing the corn field while their mother cooked.“Yo daddy ploughs ole massa’s corn. Yo mammy does the cooking; She’ll give dinner to her hungry chile, When nobody is a looking” (Sutton)So is corn in and of itself good or is it bad? Yes.

Susan Elliott

Independent Researcher

—————-

WORKS CITED

Cherniwchan, Jevan and Juan Moreno-Cruz. “Maize and precolonial Africa.” Journal of Developmental Economics. 136 (2019) 137-150. https://reader.elsevier.com/…/sd/pii/S0304387818303195…

“Human History.” Millers River Watershed Council. Accessed 1 Jan. 2021. https://millerswatershed.org/human-history/

O’Leary, Matthew. “Maize: From Mexico to the World.” The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, 20 May 2016. Accessed 30 Dec. 2020. https://www.cimmyt.org/blogs/maize-from-mexico-to-the-world/

Sutton, Katie. “Three Slave Lullabies.” The Feminist Sexual Ethics Project, Brandeis University. https://www.brandeis.edu/…/lullabies/three-lullabies.html. Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938, Indiana Narratives, Volume V “A slave mammy’s lullaby, p. 195. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mesn&fileName=050/mesn050.db&recNum=199&itemLink=D?mesnbib:1:./temp/~ammem_lIJL::

Worcester County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1731-1881. Online database. AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2015. (From records supplied by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives.) https://www.americanancestors.org/…/28660-co18/52090479

ILLUSTRATION

“Human History.” Millers River Watershed Council. Accessed 1 Jan. 2021. https://millerswatershed.org/human-history/—–