Revised 22 Sept. 2022

Bess Corbett enslaved

Mother, Father, siblings too

By the “good” doctor.

You might never have heard of Bess Corbett, but she left an indelible mark. She was the subject of a lawsuit brought in 1819 by the town of Milford against the town of Bellingham for the cost of her care in her final years. At that time, a former slave in Massachusetts was to be provided for by the place of her last enslavement when no longer able to provide for herself. We will use what we learn from the depositions taken for the trial to eke out as much we as can about Bess and will attempt to shed some light on what her life was like. She was also the subject of another essay on this website, “The Burdens of Bess Corbett.”

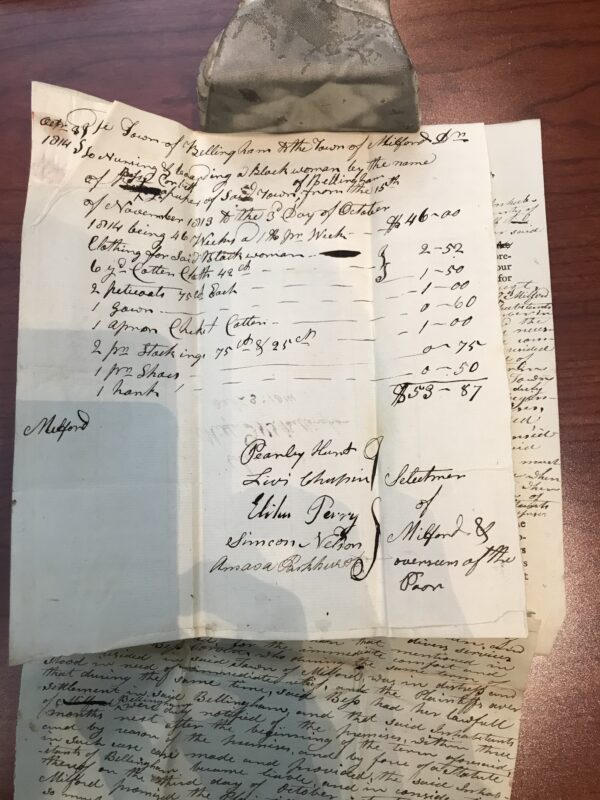

The town of Milford in 1819 was seeking reimbursement for her board and for “nursing” her, as well as for her use of six yards of cotton cloth, two petticoats, a gown, a checked cotton apron, two pairs of stockings, a pair of shoes and a handkerchief, for a total of $53.87. The bill was signed by the “Select Men” and the Overseers of the Poor in the town (Mass. Archives) (See full transcription below). It was their contention that Bellingham was the last place of her enslavement.

By the time the case reached the Supreme Judicial Court in Worcester from a lower court, the question to be decided was simply, where was her legal settlement? In other words, where was she last enslaved (“Inhabitants”)? The town judged to be so would be responsible for her expenses.

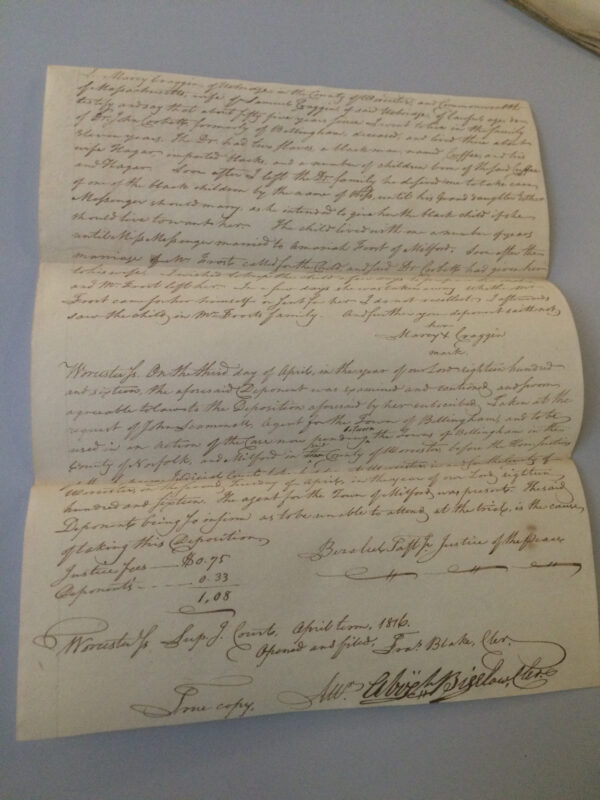

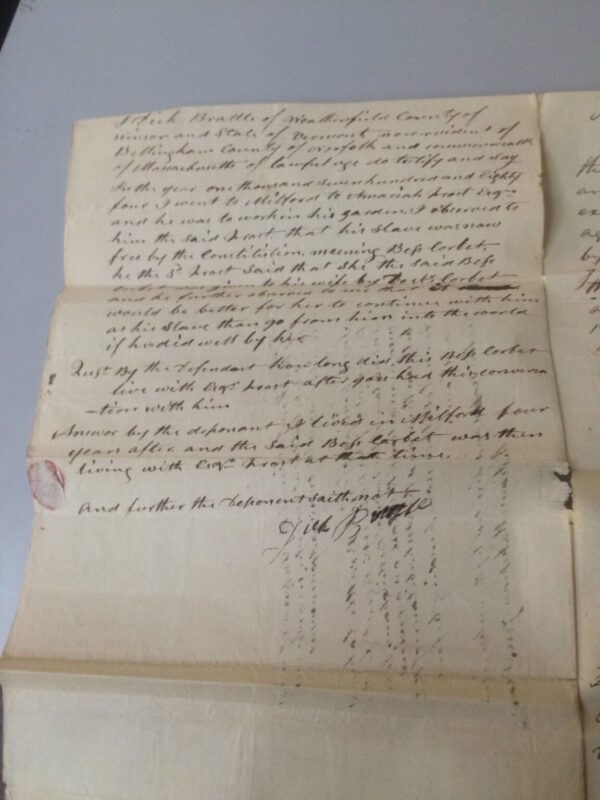

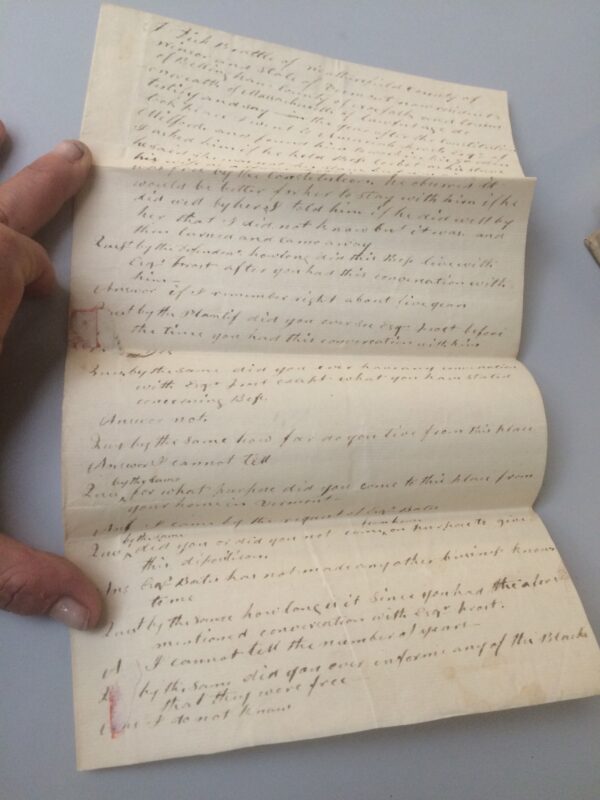

Fortunately, the Massachusetts Archives has in its collection several (if not all) of the depositions taken in the case. Depositions available include that of Dick Brattle, a man who had been previously enslaved in Bellingham, that of Amariah Frost, Jr., who was Bess’ last known enslaver, and two other people.

Now let’s see what we can learn about Bess from the four depositions and a slave census. One of the deposers was Marcy Craggin of Uxbridge. According to her testimony, Dr. John Corbett of Bellingham had made arrangements for Marcy to keep Bess in her household until John’s granddaughter married, at which point in time she would be gifted to the newlywed. Thanks to Marcy’s deposition, we also know the name of Bess’ parents, if only their given names, Hagar and Cuffee. You will note no surnames associated with the two. The enslaved rarely had last names, as they were considered chattel property, like farm animals or work tools, personal possessions.

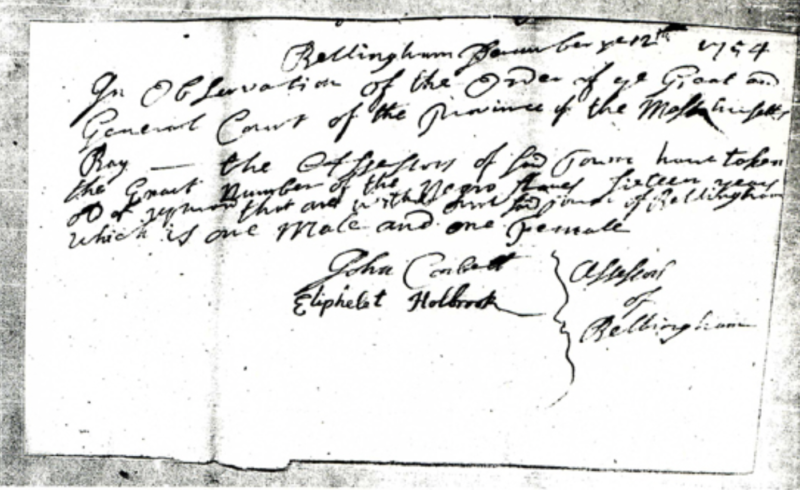

A slave census may have given us another clue as to Bess’s life that was taken in 1754, although before Bess was born. When Massachusetts needed to raise additional funds to pay for expenditures from the French and Indian War, the governor, William Shirley, called for the census. The reason? As personal property, owners of the enslaved men and women were subject to a tax, similar to an excise tax. And although the return states that there was only one male and one female slave sixteen years old or older in Bellingham, that did not include children, the old or infirm. Since the births of the enslaved were mostly undocumented, there may have been older teenagers that passed (or were passed along) as younger as well. However, the man and the woman might have referred to Hagar and Cuffee. Assigned only to a number, “one Male and one Female,” we likely will never know.

“Bellingham December ye 12th 1754 In Observation of the Order of ye Great and General Court of the province of the Massachusetts Bay —the assessors of said Town have taken the Exact Number of the Negro slaves Sixteen years old [and older] […] which is one Male and one Female.”

Bellingham return of 1754 Massachusetts Bay slave census.

We learn a couple of other things from Marcy about Bess’ parents, Hagar and Cuffee, from her time living and working in the Corbett household. For one, the two were “imported blacks,” meaning they were not born in the future United States, but possibly in the West Indies or Africa. Secondly, Bess apparently had several siblings. Marcy stated that there were “a number of children born of the said Cuffee and Hagar ”in the household of Dr. John Corbett of Bellingham. That is where Bess was enslaved before being given away to Amariah’s wife, Esther Messenger, one of John’s granddaughters. You can glimpse where John set his pen to paper in the 1754 slave census return included in this article [See above]. Why? He was one of the assessors for the town of Bellingham.

Other clues we can glean from Marcy’s testimony come from Bess’s father’s name, Cuffee. Cuffee is a name given to male children born on a Friday in some cultures along the Gulf of Guinea of west Africa, a common location for the historic international slave trade, also known as the Triangular Trade.

(Wikimedia)

The day of the week naming of newborns is and was part of many African cultures, and the name Kofi (also spelled Cuffee) is found among the Agni of the Ivory Coast [Côte d’Ivoire], the Baule of the Ivory Coast and Ghana, the Gen of Togo, the Efi of Benin and Togo, the Fanti of Ghana and the Twi of Ghana. Since Marcy testified that Cuffee was an “imported black,” it is not unlikely that Bess’s father or his parents were kidnapped and sold into slavery from either the Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo or Benin, a long way from Bellingham (Stewart).

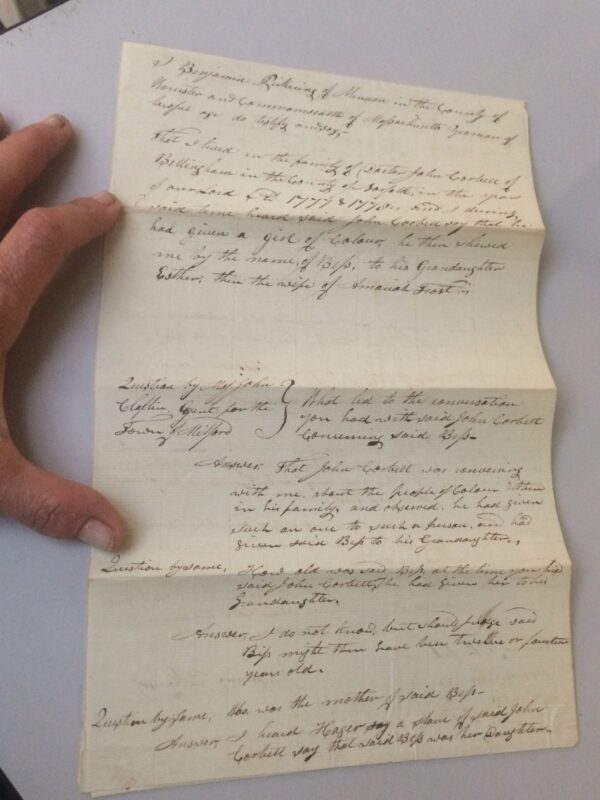

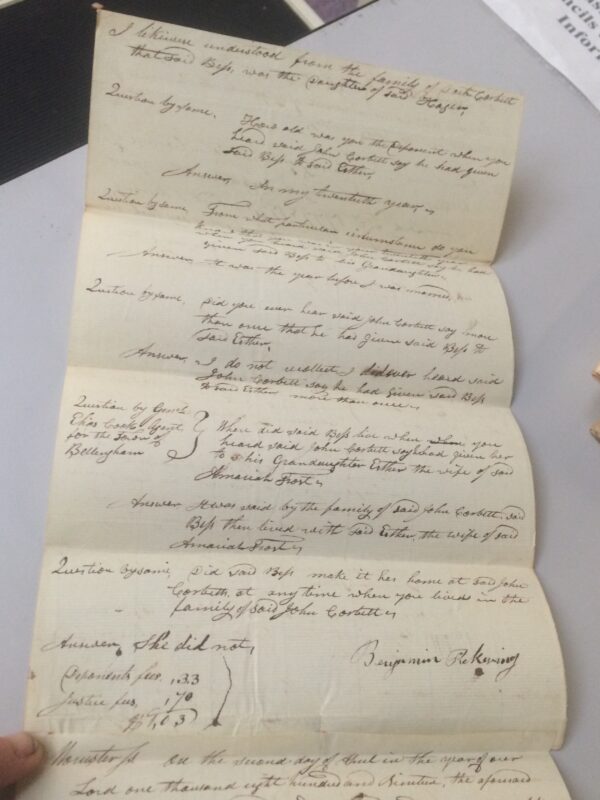

In another deposition from the trial, Benjamin Pickering of Mendon testified that he had also lived with John, in his case in 1777 and 1778. Among other things, he had the following to say:

“I Benjamin Pickering of Mendon in the County of Worcester and Commonwealth of Massachusetts Yeoman of lawful age do testify and say, – That I lived in the family of Doctor John Corbett of Bellingham in the County of Norfolk in the year of our Lord AD 1777 & 1778, and I during said time heard said John Corbett say he had given a girl of Colour, he then shewed me by the name of Bess, to his Granddaughter Esther, then the wife of Amariah Frost.”

Like Marcy, Benjamin also testified that Bess was Hagar’s daughter, although there was no mention of Cuffee or the children in his deposition. His source? Bess’ mother, Hagar, as well as John’s family. By the time Benjamin lived with John, Bess was already living in Milford with Amariah. John had told him about his giving away of Bess to his granddaughter, Esther.

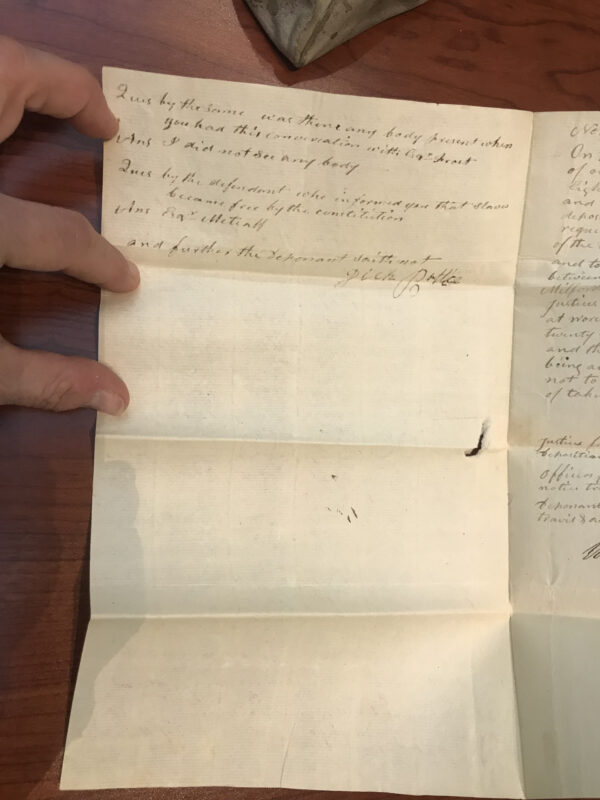

Dick Brattle, like Bess, had been enslaved in Bellingham (Brattle). He came to Bess’ defense in 1784, according to his testimony in the trial, informing her owner at the time, Amariah, that the slaves had been freed in Massachusetts due to the Massachusetts constitution. However, Amariah was unmoved according to Dick’s deposition. When Dick moved from the area four years later, she was still living in Milford within Amariah’s household.

Besides both having been enslaved in the same town, Dick and Bess had something else in common, they had been given away at very young ages, Dick at two weeks old (Brattle) and Bess sometime between her sixth year and her fourteenth (see NOTE). As the Reverend John Eliot of Massachusetts wrote in 1795 to Jeremy Belknap,

“Lover & friends were separated & their children given away with the same indifference as little Kittens & young puppies” (Eliot).

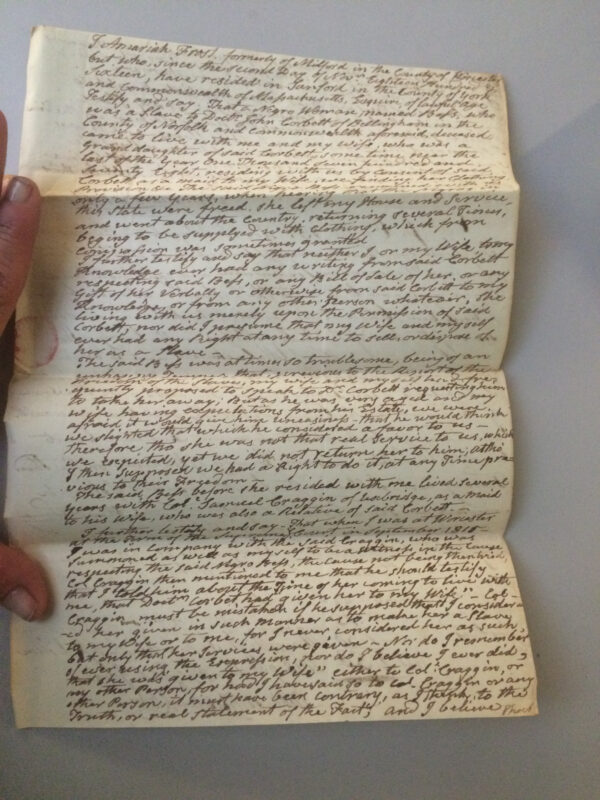

The fourth and final deposition we will take a look at to learn more about Bess was given by Amariah. John was long gone by the time the court case came around so we do not have the opportunity to learn from him. However, with several enslaved people as free labor, we may consider crediting them with helping John to end his life with an impressive amount of real estate (Norfolk) [Link to transcribed probate inventory].

Everyone whose deposition is available to us in the case of Milford versus Bellingham remembered Bess as having been given away to Amariah’s wife as a gift from his father-in-law John, except for Amariah. Amariah claimed that,

“The Services of the said Bess were of so little Benefit to my Family that had I considered her as my Slave, I think I should have attempted to have sold her in the Time I supposed the Negros were held as Slaves.”

Amariah Frost Jr.

He went on to say that she “was at times so troublesome, being of an unhappy Temper” (Frost). Unhappy about being a slave? Is it any wonder? She was only one of a myriad of people enslaved throughout Massachusetts and elsewhere who were of “an unhappy Temper.”

Not surprisingly, sometimes “an unhappy Temper” led to the murder of an owner. For example, in the abutting town of Mendon in 1745, Jeffrey (no last name) was convicted of the hatchet murder of Tabitha Sandford, the wife of his owner, Reverend Thomas Sandford (Homicides). Jeffrey, who made no attempt to leave the area, was executed soon after.

In another murder, Mark Codman, stolen from his home country, had come to enjoy living with his family in Boston after agreeing to hand over his wages to his owner, John Codman. That worked until Mark was warned out of the city, and was called back to John’s place without being able to bring his family. They had been sold off or given away outside the area (Lemire 41-69). In the end, Mark and his sister, Phillis, were both executed for facilitating Codman’s death, Mark procuring the poison and his sister administering it.

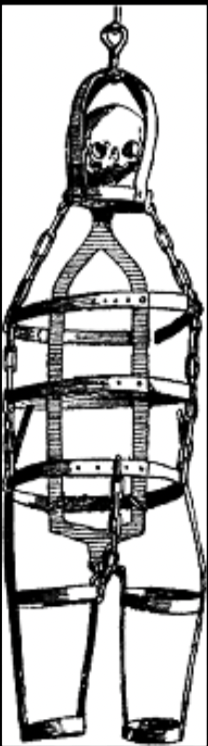

[ILLUSTRATION of a gibbet: William Andrews]

Paul Revere, years later, wrote of riding by the gibbeted remains of Mark just north of the Cambridge common, left as a warning to the enslaved on what became famously known as his midnight ride (Rodwin). Fortunately for Amariah, Bess only displayed “an unhappy Temper.”

In Bess’s own way, perhaps she helped to end slavery in the state. One of the reasons that the practice gradually disappeared, according to John Adams was the following:

The common white People, or rather the labouring People, were the

cause of rendering Negroes unprofitable servants. Their Scoffs and Insults, their

continual Insinuations, filled the Negroes with Discontent, made them lazy

idle, proud, vicious, and at length wholly Useless to their Masters: to such

a Degree that the Abolition of slavery became a Measure of Oeconomy (Adams).

Whether Adams was correct in his assessment or not, in the end, Bellingham prevailed over Milford. Amariah’s defense that there was no bill of sale and therefore ownership had not been transferred from John failed. As for Bess, her trail ends here for us, at least for now. Like the rest of her family, the place of her burial is unknown.

However, we do know that Amariah was buried in Springvale, New Hampshire (Find). On his tombstone reads the following:

“No pain, no grief; no anxious fear, Invade thy bounds; no mortal woes Can reach the peaceful sleeper here, Whilst angels watch its soft repose.” – Dr. Isaac Watts. (Hymn 262, page 211).

Ironically, these words were compiled into a hymnal by Jeremy Belknap, a man who successfully presented a petition to the General Court in 1788 to end the slave trade in Massachusetts and who was a member of the Society for Abolishing the Slave Trade in Rhode Island (Belknap).

Let’s end Bess’s story today with a photograph of the Bellingham house where she lived and slaved alongside her family, as a remembrance of her and her kin.

(Photo appears in George Partridge’s book, History of the Town of Bellingham, published in 1919. The house was demolished many years ago. The address of the location is today’s 3 Grove Street.

Susan Elliott

Independent Researcher

Website: EnslavedNewEngland.org

Facebook: Hosea of Franklin, Massachusetts

N.B. If additional sources or interpretations are discovered, they may affect the conclusions in this article.

Works Cited

1754 Slave Census. Primary Research.

Adams, John. “Letter from John Adams to Jeremy Belknap, 21 March 1795.” Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online.

“Belknap, Jeremy.” Harvard Square Library. Accessed 18 Sept. 2022.

Brattle, Dick. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application File

R. 1167, Dick Brattle, Conn. Mass. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/54040531

Cambridge Historical Society. Publications VIII, Proceedings January 28, 1913 to

October 28, 1913. https://archive.org/details/publications07masgoog/mode/2up

Eliot, Reverend John. “Letter from John Eliot to Jeremy Belknap (on printed circular

with queries about slavery in Massachusetts.” Massachusetts Historical Society. https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=575

Find A Grave. Amariah Frost (Junior) (1750-1819). Created by Eric McGuire.

Frost. deposition

“Gulf of Guinea Nations.” Wikimedia Commons. Screenshot taken 5 Sept 2022.

Harkness, O. A map of the town of Milford, Worcester County, Massachusetts. S.l: s.n.,

1851. Web. 14 Sep 2022. https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/1257bb71d.

Homicides of Adults in Massachusetts, 1741-1750. Criminal Justice Research Center.

The Ohio State University. https://www.osu.edu

“Inhabitants of Milford (MA) vs. Inhabitants of Bellingham.” Caselaw Access Project.

Harvard University. 16 Mass. 108, 15 Tyng 108 (1819), Sept. 1819, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. https://cite.case.law/mass/16/108/

Lemire, Elise. Black Walden, Slavery and Its Aftermathin Concord, Massachusetts.

University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009, Philadelphia.

Massachusetts Archives. “Inhabitants of Milford, Massachusetts vs. Inhabitants of

Bellingham, Massachusetts.” Supreme Judicial Court, Worcester County, September 1819.

Norfolk County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1793-1877.

AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2019. (From records supplied by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives. Digitized images provided by FamilySearch.org) https://www.americanancestors.org/DB2739/i/51353/4476-co13/71040801

Partridge, George Fairbanks. History of the Town of Bellingham, Massachusetts,

1719-1919. Town of Bellingham, 1919. https://archive.org/details/historyoftownofb00part/page/50/mode/1up

Rodwin, Nina. “‘Mark Hung in Chains:’ Slavery & Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride.” https://www.paulreverehouse.org/mark-hung-in-chains-slavery-paul-reveres-midnight-ride/

Stewart, Julia. 1,001 African Names, First and Last Names from the African Continent.

Citadel Press, 1996, New York, N.Y.

Watts, Isaac. “Hymn 262.” Hymnal edited by Jeremy Belknap. Thomas Wells, 1812,

Boston.

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Gulf of Guinea Nations.png,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Gulf_of_Guinea_Nations.png&oldid=496658778 (accessed September 18, 2022).

William Andrews. Gutenberg Project : E-text prepared by Eric Hutton, Stephen Blundell, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team – William Andrews (1848-1908), Bygone punishments, London : W. Andrews & co., 1899, p. 49. Scanned illustration for the From the Gutenberg Project edition

Octer 3d 1814. To nursing and boarding a black woman by the

name of Bess Corbett, a pauper of said Town of

Bellingham, from the 15th of November, 1813, to the

3d day of October 1814, being 46 weeks, @ $1. pr week. $46.00

Clothing for the said black woman 6 yd Cotton Cloth

At 42 cts 2.52

2 petticoats, 75 cts each, 1.50

1 Gown 1.00

1 Apron, checkt cotton 0.60

2 pr Stockings. 75 cts @ 25 cts 1.00

1 pr Shoes .75

1 Handk: .50

Milford — $53.87

Pearley Hunt

Levi Chapin

Elihu Perry Select Men of Milford & Overseers of the Poor

Simeon Nelson

Amasa Parkhurst

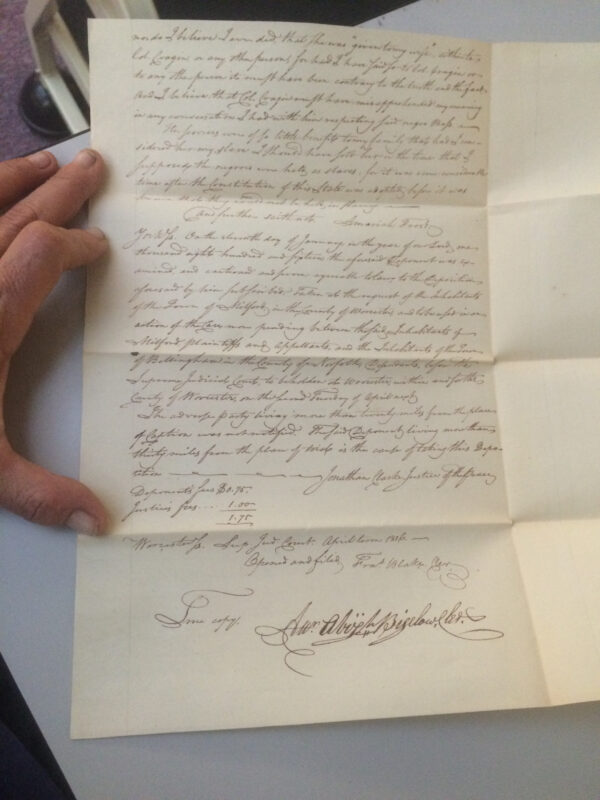

True copy. (illegible signature) Abijah Bigelow (?)

SOURCE: Transcribed from manuscript at Mass. Archives in person (photo taken)