When John Adams was a young man of only 25 years of age, the future president made merry with the best of them in the town of Braintree outside of Boston. As he wrote in his diary back in 1760: “[W]ent to smoke a Pipe, at Ben. Thayers, where the Rabble filled the House. Every Room, kitchen, Chamber was crowded with People. Negroes with a fiddle. Young fellows and Girls dancing in the Chamber as if they would kick the floor thro” (John).

Adams may have heard the song, “Pompey Ran Away,” while he was at Benjamin Thayer’s tavern. The song was later transcribed and published as a “Negroe jig” during the Revolutionary War, and believed to be rooted in African music. Pompey was a common name given to enslaved men. [Have a listen thanks to Colonial Williamsburg: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZw54ruLXYw]

A few years earlier, in 1753, a different Pompey sought freedom on foot. We know quite a bit about him because of the run-away advertisement his enslaver posted about him in the Boston Evening Post after his escape. A man of around forty years, he prepared well for a new life beyond Dunstable by taking with him plenty of clothes by that day’s standards, including a “Homespun grey Coat with yellow Metal Buttons,” a couple of jackets, some light blue breeches, two shirts, one linen, the other woolen, as well as stockings, and a pair of “pumps,” a type of colonial shoe (Advertisement).

Despite having a finger that was “reckoned to be so crooked that he cannot hold it straight,” the advertisement went on to say that Pompey played the violin. He was likely one of the many enslaved Black men throughout the American colonies by the mid-1700s who performed at the social events of whites, in town and country alike (Jamison).

Among the many legally bound Black fiddlers in New England, there was Cyprian, enslaved in the Massachusetts town of Harvard. He was said to be “a born fiddler [who] had furnished the musical inspiration and called the dance figures for all the rural junketings in his neighborhood.” Shortly before Cyprian died, reputedly at over ninety in 1784, he broke his violin into bits so that there would be no ‘quarreling over his estate after he was gone’” (Nourse). The instrument was clearly treasured by him and others.

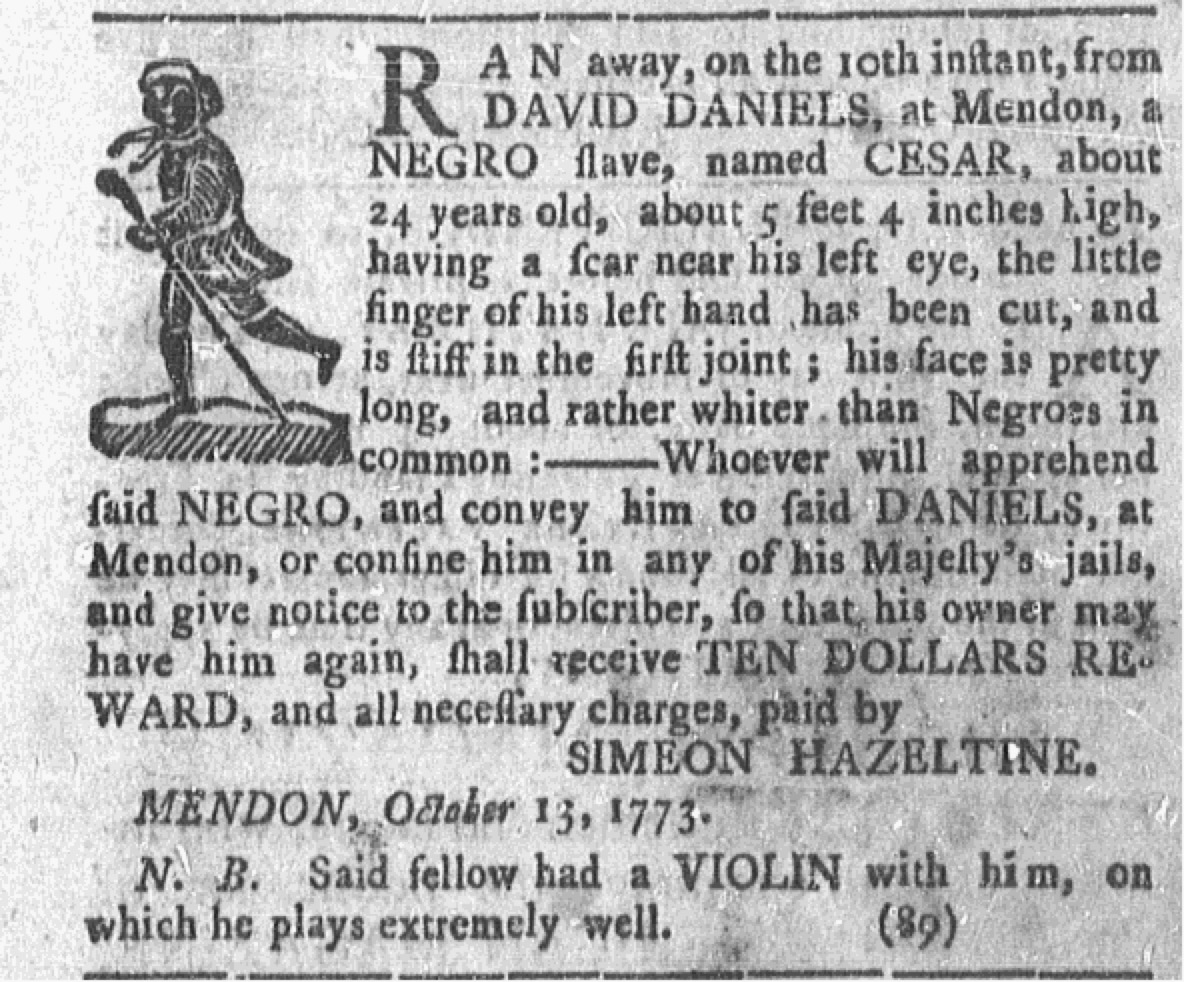

There was Cesar, another fiddler, who undoubtedly traveled on some of the same roads I ramble and ride on from my 1720s home in today’s Milford, then part of Mendon. Cesar escaped his servitude and within a month his enslaver placed an advertisement for his return. Like Pompey, he also suffered an injury to a finger, the pinkie of his left hand which was “stiff to the first joint.” [See this accompanying advertisement] But what David Daniels chose to emphasize in the ad copy was the following:“N. B. Said fellow had a VIOLIN with him, on which he plays extremely well.” (Newport).

We will likely never know who the Black fiddlers were that livened the crowd at Thayer’s tavern that summer’s night long ago young Adams enjoyed, be they a Pompey, a Cyprian, a Cesar, or otherwise named. But we do know that these gentlemen may have been carrying on the long standing tradition of West Africa whose “musical traditions (including fiddling) were firmly in place before the transatlantic slave trade began” (Diedje). Susan ElliottIndependent Researcher—–

WORKS CITED

“Advertisement.” Boston Evening-Post, no. 935, 30 July 1753, p. [2]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A1089C792E64CF650%40EANX-108EC01ECE83E1A0%402361541-108EC01F043AA828%401-108EC01FA82D6298%40Advertisement. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

DJEDJE, J. (2016). The (Mis)Representation of African American Music: The Role of the Fiddle. Journal of the Society for American Music, 10(1), 1-32. doi:10.1017/S1752196315000528 https://www.cambridge.org/…/63166A546740B55B8D3E845ACEB…

Jamison, Philip A. “Square Dance Calling: The African-American Connection.” Journal of Appalachian Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, 2003, pp. 387–398. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41446577. Accessed 14 Nov. 2020.John Adams diary 5, 26 May – 25 November 1760 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society. http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/

Newport Mercury, no. 791, 1 Nov. 1773, p. [4]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A106AD2C0F76EDF48%40EANX-1070279591AB5890%402368940-107027962D7DA528%403. Accessed 5 Dec. 2020.

Nourse, Henry S. History of the town of Harvard, Massachusetts, 1732-1893. 2005.