There is nothing new about wild conspiracy theories, misinformation and misunderstandings. They are all as old as humankind.

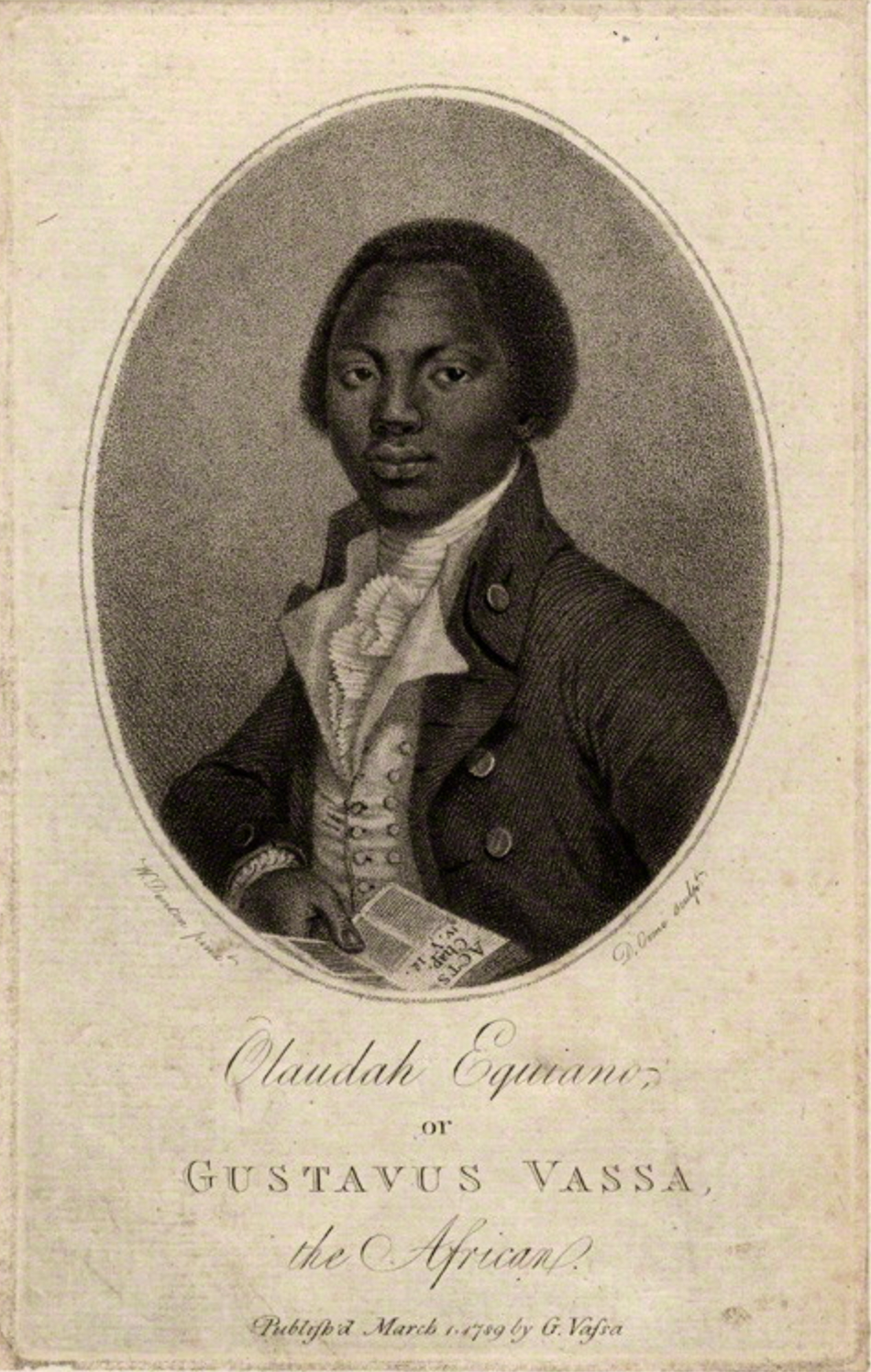

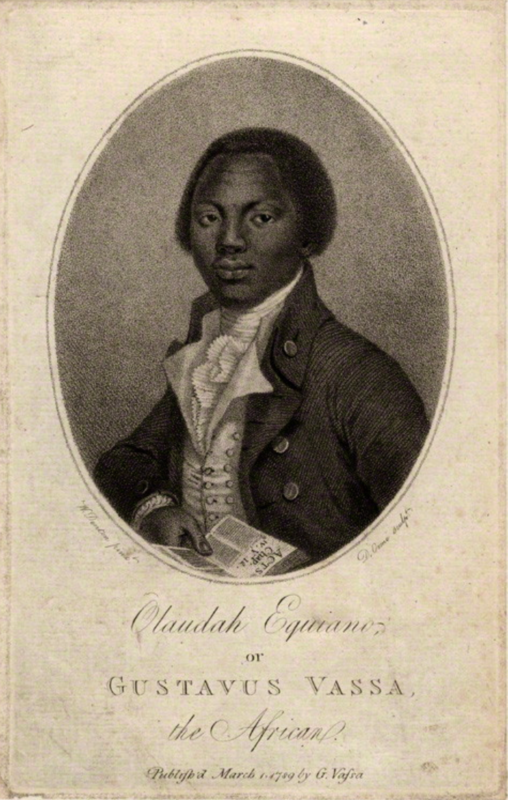

Olaudah Equiano was just eleven in 1756 when he was stolen from his West African family’s home and shipped to the Americas. On the way, the food stocks became exceedingly low. The captain and others joked that the enslaved were going to be eaten next. The humor as passed along was lost on Olaudah. He was terrified, as he wrote in his memoir years later:

“They put us in separate parcels, and examined us attentively … We thought by this we should be eaten by these ugly men, as they appeared to us; and, when soon after we were all put down under the deck again, there was much dread and trembling among us, and nothing but bitter cries to be heard all the night from these apprehensions” (Equiano).

Here’s another case of misinformation. It was rumored that sharks were foreign to the eastern shores of New England. The sharks, it was believed, traveled for the first time in the wake of slave ships in a grisly migration.

“These man-eating sharks are not now, and were not then, indigenous to our shores, but followed in the track of slave ships from the Guinea coast; a number of Bristol and Newport [Rhode Island] ships then being engaged in the slave trade” (Cole 555).

Not true. Sharks have roamed the oceans for hundreds of millions of years and survived not one, but five mass extinctions, including the one that destroyed most of the dinosaurs (Davis). Surely they had found their way in the past. A case of misinformation (Ocean).

Then there is the story of the slave ship Zong. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston holds a painting titled “Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On)”(Turner). According to the museum’s website, the painting is based partly “on the true story of the Zong, a British ship whose captain, in 1781, had thrown overboard sick and dying enslaved people” (MFA).

The truth is even worse. It was not the “sick and dying” who were known to have been thrown overboard.When the ship’s owner filed a claim against the loss of the Africans “lost at sea,” the insurance company refused to pay, and a trial soon occurred. It is from the court records that we get closer to the truth of what transpired on the slave ship.

There were three sets of murders on the one trip.

On November 29, 1781 fifty four women and children, not the “sick and dying,” were thrown overboard.

On December 1, forty-two “stout healthy Men slaves,” again not the “ sick and dying,” faced the same fate.

Sometime after December 6, 36 more Africans were either thrown off the ship or committed suicide by jumping off. We do not have a record of the condition of the people who died that day.

Which brings us back to the official write up of the painting. What could be worse than throwing the “sick and dying” overboard? Throwing just about anyone and everyone of color overboard [For more details on the fatal voyage, read Bernard Trevor’s well researched essay, “A New Look at the Zong Case of 1783.” Link below].

Which brings us back to Olaudah Equiano, also known as Gustavus Vasa, whom we left as a youth. He alerted a leading London abolitionist, Granville Sharp, of the mass murders on the slave ship.

“March 19, [1783]. Gustavus Vasa, a Negro, called on me, with an account of one hundred and thirty Negroes being thrown alive into the sea, from on board an English slave ship” (Bugg 236).

The Zong murders helped galvanize English anti-slavery forces. Whether or not Sharp would have learned of the murders at sea anyway, we still have a former slave to thank as a formidable abolitionist.

And that’s the truth.

Susan Elliott

Independent Researcher

—–

WORKS CITED

Bernard, Trevor. “A New Look at the Zong Case of 1783. XVII-XVIII [En ligne], 76 | 2019, mis en ligne le 31 décembre 2019, consulté le 13 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1718/1808; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/1718.1808

Bugg, John. “Equiano’s Trifles.” ELH 80, no. 4 (2013): 1045-1066. doi:10.1353/elh.2013.0042.https://www.fordham.edu/…/id/8420/equianos_trifles.pdf

Davis, Josh. “Shark evolution: a 450 million year timeline.” Natural History Museum at South Kensington. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/…/shark-evolution-a-450-million…

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, The African. Written by Himself. Project Gutenberg, March 17, 2005 [EBook #15399]. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15399/15399-h/15399-h.htm The year and Equiano’s age at the time of his capture was found in the following: Piersen, William D. “White Cannibals, Black Martyrs: Fear, Depression, and Religious Faith as Causes of Suicide Among New Slaves.” The Journal of Negro History 62, no. 2 (1977): 147-59. Accessed December 13, 2020. doi:10.2307/2717175.

Museum of FIne Arts (MFA). https://collections.mfa.org/objects/31102

Ocean Portal Team. “Sharks, Euselachii.” Smithsonian Ocean. https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/sharks-rays/sharks

Turner, Joseph Mallord William. Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On). 1840, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

ILLUSTRATION

Olaudah Equiano. Encyclopædia Britannica. The British Library. https://www.britannica.com/…/Olaudah-Equiano/images-videos